A Primer on Recognition Primed Decision-Making (RPD)

Experts don’t compare a list of options—they recognize patterns, simulate outcomes, and act quickly, which is why the RPD model emphasizes experience-based intuition instead of teaching abstract decision theory.

“This is going to be a short interview. I don’t make decisions.”

So began Gary Klein’s first interview with a fire chief1. Gary and his team had decided to study firefighters as part of a research grant to study decision-making in high-stakes environments. But Gary’s heart dropped when the fire chief insisted he didn’t make decisions. This was going to be a problem.

Gary asked for further clarification, and the chief responded that he just followed protocol. But when Gary asked to see that protocol, the chief admitted, “It’s not written down.”

What was going on here? If experts like firefighters aren’t choosing between options nor following explicit protocol, how do they manage the complex, uncertain, high-stakes situations in which they find themselves?

This puzzle led to the development of the Recognition-Primed Decision (RPD) model, which has since transformed how we understand real-world decision-making. In this article, I’ll explain what RPD is, how it works, how it compares to traditional models, and what it implies for training and expertise.

What is in a decision?

Every once in a while, you might come across someone trying to estimate how many decisions people make in a day. Some of these estimates will say 10, while others will say 10,000. It turns out that nobody agrees because no one even agrees on what a “decision” is.

Take a simple example: You make some buttered toast. During that process, did you decide to use the toaster instead of the microwave? Did you choose to get the knife before the butter? If you are (or are not) trying to answer these rhetorical questions right now, did you decide to do that?

You can start to see the firefighter’s dilemma. In the lab, researchers typically define decisions as a choice between options. But the real world doesn’t hand you options like some multiple-choice test. Instead, you have to construct your options in the moment. And oftentimes, in the real world, before you even realize what you are doing, you have already constructed an option and acted on it. It may feel like protocol, but that is only because your past experience allows you to do this seamlessly and without much thought.

It is the same with highly experienced experts in many diverse domains, such as firefighting.

The RPD model

When Gary and his team set out in the 1980s to study firefighters, they found that even during situations they described as challenging, experienced firefighters couldn’t recall making any decisions. As you might imagine, this proved quite the complication for their study on decision-making.

But just because the firefighters were not deliberating between options doesn’t mean that what they were doing was simple and straightforward.

Instead of the methodical approach to decision-making often taught in business schools, they used pattern recognition. They would see a situation and match it to similar ones they had experienced before, which would help them know what to do. Typically, there was not a specific situation they recalled, but rather a prototype of a situation—just as you don’t recall a specific instance of toasting bread when you decide to use the toaster. This match-and-act process is the core of the Recognition-Primed Decision (RPD) model. It is the first of two major components, or loops, within the RPD model.

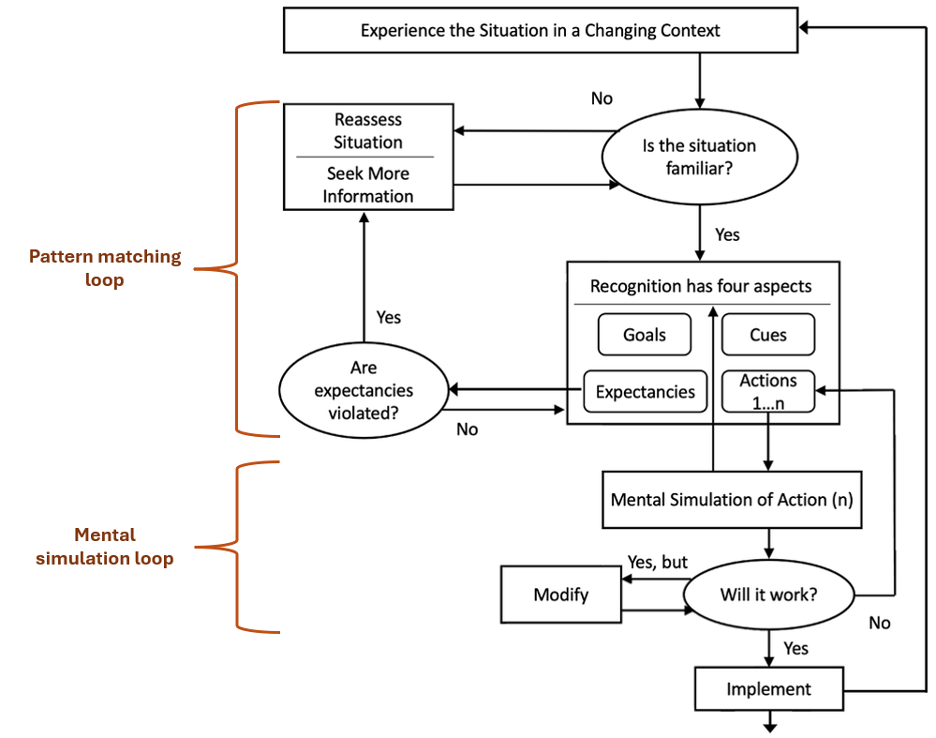

- Pattern Matching Loop

The decision-maker identifies a situation as familiar, and that pattern highlights relevant cues, plausible goals, expectancies, and typical actions. They reassess and search for more information if the situation doesn’t match expectations. But if it does match, they move on to the next step.

This second loop within the model is about evaluating the action considered. Such evaluation is not always necessary, but experts often do so to ensure they are not forgetting anything and can anticipate what will happen. We can call this the Mental Simulation loop.

- Mental Simulation Loop

The decision-maker imagines the likely outcome of the action. If it checks out, they proceed. If not, they might modify the action or reassess the situation. Or, if they can’t find a decent modification, they move on to the next course of action in their repertoire. This is not an exhaustive pros-and-cons evaluation, but a fast simulation of the action and its consequences based on the decision-maker’s understanding of the situation and the world.

This method of decision-making can make these domains difficult to study. How do you even define the meaningful decision points if every action, one after the other, is just pattern matching to similar relevant prototypical situations?

To address this, Gary and his team decided that the best way to define a decision point was to ask about moments where a novice could have chosen to act differently than the expert. This helped the research team focus on situations where everyday pattern matching and common sense are insufficient but require some experience or training.

Once decisions were defined this way, the team identified 134 decision points in their studies, 117 of which were made using RPD. Most of the non-RPD decisions were made during one particularly difficult multi-day case where the firefighters lacked experience and had to call in outside consultants. This is far from a typical case and not overly relevant if your goal is to train high-stakes decision-makers.

Since then, other research has further supported the conclusion that experts in diverse domains—soldiers, athletes, law enforcement, and fighter pilots—make most of their decisions in the way described by RPD.

Challenging traditional decision models

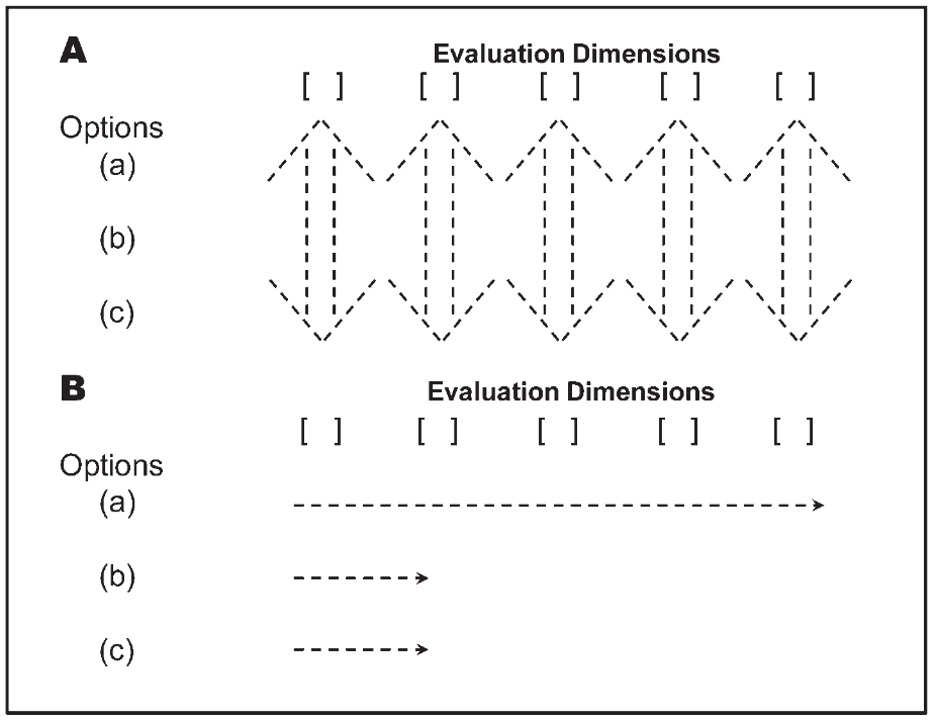

Most classical decision-making models are built on deliberation: generate options, weigh their trade-offs, and choose the one with the best expected value.

Take Kahneman’s Mediating Assessments Protocol2, which instructs decision-makers to generate all options and score them dimension by dimension based on measurable criteria. Such an approach might make sense in low-pressure, spreadsheet-based contexts, but collapses in high-stakes, time-pressured situations. In the study of firefighters, 78% of decisions were made in less than 1 minute or even under 30 seconds–Not nearly enough time for such deliberative approaches.

In the real world, options aren’t always clear. Decisions often happen before people realize they have a choice. That’s why Klein and his team found “virtually no instances of the standard laboratory paradigm” among expert firefighters. If multiple options were even considered—which they often are not—they were evaluated serially, not in parallel. Experts would think of one option, reject it, and then move to another—not compare all of them side-by-side.

This tracks with research in other domains. Expert chess players, for instance, often perform just as well under speed conditions. How is this possible? Because they’re not consciously evaluating each possible move across many dimensions—they’re matching the current board to one of the thousands of patterns they’ve internalized through years of play. If the first move you consider is good enough, why consider any other? You’re just wasting time.

Challenging Heuristics and Biases

Another major field of decision research is called Heuristics and Biases, which often studies all the ways our intuition can go wrong. At first glance, RPD may seem incompatible with their research findings since RPD shows how intuition can go right. So it is worth thinking about where the two meet.

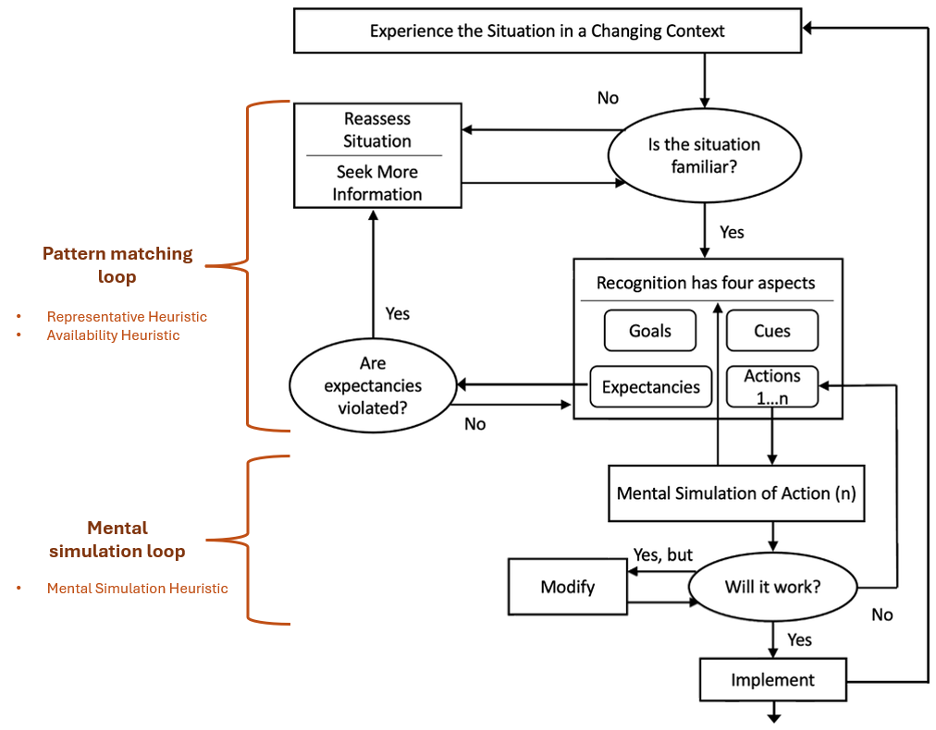

One important consideration is that RPD is a macrocognitive model—consisting of multiple cognitive processes chained together into a much more complex process. One way of thinking about it is that it consists of three distinct heuristics (rules of thumb), all of which have been well-studied by the Heuristics and Biases research community:

- Availability Heuristic → Helps the expert recall similar past experiences

- Representative Heuristic → Helps match the current situation to a known prototype

- Mental Simulation Heuristic → Helps imagine the consequences of an action

A major issue with these heuristics is that they each require experience to function adaptively. RPD works because experts have years of experience and can identify relevant representative prototypes and mentally simulate situations based on their thorough understanding of the context and the world. Compare this to undergrads doing novel research experiments in a lab who have no relevant past experience to rely on—the typical set-up in most Heuristics and Biases studies. These heuristics will inevitably fail in such cases as the subjects have not experienced the appropriate conditions for developing intuitive expertise3.

Additionally, just like individual lines of code are hard to assess outside the context of the rest of the code base, individual heuristics are difficult to make sense of outside the context of the rest of the heuristics being used. A macrocognitive model cannot be judged by its individual parts but by how those parts operate together to accomplish something far more than any of its individual parts.

In short, if you study decision-making outside of both its environmental and cognitive context, decision-makers will look quite error-prone. However, such errors are not representative of real life. Even the failures of real-life decision-making will look quite different than those in a lab because heuristics may feed off and into each other in ways not well understood by typical research methods. This is the major reason decision-making must be studied in naturalistic settings where a more complete picture can come into view.

Conclusion

A common misconception is that intuition only helps with trivial decisions. In a now-famous exchange about the rationality of intuition, economist Ken Binmore argued that intuition becomes more rational over time as people learn from their mistakes. Richard Thaler, founder of Behavioral Economics, pushed back. Sure, he said, that might work for something like grocery shopping because we do it every week. But there isn’t enough feedback for major life decisions like marriage or retirement. Thaler claimed victory with a quip: Binmore’s highbrow theories about the rationality of intuition were only good for “buying milk.”4

But not all intuitive decisions are as trivial and mundane as toasting bread or buying milk. In many high-stakes fields—military, industrial safety, medicine, law enforcement—professionals routinely make life-or-death decisions, and they rely on intuition to do it. There can be enough feedback for expert intuition to form in these domains. In these domains, intuition isn’t a flawed shortcut but a skill that can be trained.

Another misconception is that intuition is mystical. Experts themselves will sometimes say they have ESP or a spidey sense. But there’s nothing supernatural about it. What can sometimes look like a sixth sense is actually just the product of the inherent human capacity to recognize patterns and simulate consequences.

This is why the best way to teach RPD isn’t to explain the model, and we rarely, if ever, do so. Instead, at ShadowBox, we train the underlying skills of pattern matching, mental modeling, and critical thinking in dynamic environments. We do that through our written ShadowBox scenarios, Tactical Decision Games such as those at Warfighters, and our ExpertEyes visual cue detection platform. We help people build intuitive decision-making from the ground up and strengthen the core skills on which RPD depends.

Because ultimately, you don’t get better at decisions by studying the theory. You get better through experience and reflection on actual decisions—whether in the field or simulated in scenarios.

References

- G. A. Klein, R. Calderwood, and A. Clinton-Cirocco, “Rapid Decision Making on the Fire Ground,” Proceedings of the Human Factors Society Annual Meeting, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 576–580, Sep. 1986, doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/154193128603000616.

- D. Kahneman, D. Lovallo, and Olivier Sibony, “A Structured Approach to Strategic Decisions,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Mar. 04, 2019. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/a-structured-approach-to-strategic-decisions/ (accessed Jun. 09, 2025).

- Kahneman, D., & Klein, G. (2009). Conditions for intuitive expertise: A failure to disagree. American Psychologist, 64(6), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016755

- “Exuberance Is Rational,” Nytimes.com, 2018. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/magazine/home/20010211mag-econ.html?module=inline (accessed Jun. 09, 2025).