Oblivious

Many talented scientists had the data needed to make sense of DNA, yet none recognized the insight that Watson and Crick eventually assembled. Gary Klein examines why leading researchers missed a breakthrough in plain sight and what their failures reveal about barriers to insight.

Why do people fail to gain insights? Perhaps we can find some ideas for increasing our insights by examining insight failures — instances in which people were oblivious to the potential insight sitting in front of them. One famous example is the comment T.H. Huxley made when he learned of Darwin’s theory of evolution, “How extremely stupid not to have thought of that.”

This essay examines Watson and Crick’s discovery of the structure of DNA and its role in genetic transmission. Let’s look at the bookend — the scientists who failed to make this discovery. Let’s see what we can learn from them. Why were they so oblivious?

Note: Some parts of this essay are cryptic because if I unpacked each detail, the essay would turn into a book. And also, because I admit that I do not fully understand many of the nuances of this story. Bear with me on these details and try to stay focused on the main takeaways. If you do want to unpack the details, a good place to start is Judson, 1996.

Background

A variety of disciplines were investigating genetic phenomena: Genetics, microbiology, physics, and chemistry. Genes were thought of as information carriers. Many, if not most, researchers at the time believed that genetic information was carried by proteins, which had sufficiently complex structures to carry the necessary information. In contrast, DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) consisted of only four bases (adenine, thymine, guanine, cytosine) and was seen as too simple to code for the variety of proteins that had to be designed by genetic transmission. DNA was thought of as playing some secondary role, perhaps as a backbone for the real process.

Avery (1944) had found that bacterial DNA embodied the bacterial genes, but most researchers thought Avery’s work lacked the necessary controls, and even Avery was reluctant to believe it. Then, in 1952, Hershey and a colleague showed that when a phage particle infects its bacterial host cell, only the DNA of the phage actually enters the cell. The protein of the phage remains outside. (“Phage” is short for “bacteriophage” — a virus that infects and replicates inside bacteria.) From the time of Hershey’s demonstration, genetic thought turned to DNA.

In addition, Chargraff had demonstrated that the four types of DNA bases do not monotonously follow each other but have a more complex arrangement, which also makes DNA interesting. It was time to study DNA more carefully, using methods such as X-ray crystallography. Linus Pauling had already used X-ray crystallography to discover the basic structure of a protein molecule. It was a single-stranded helix.

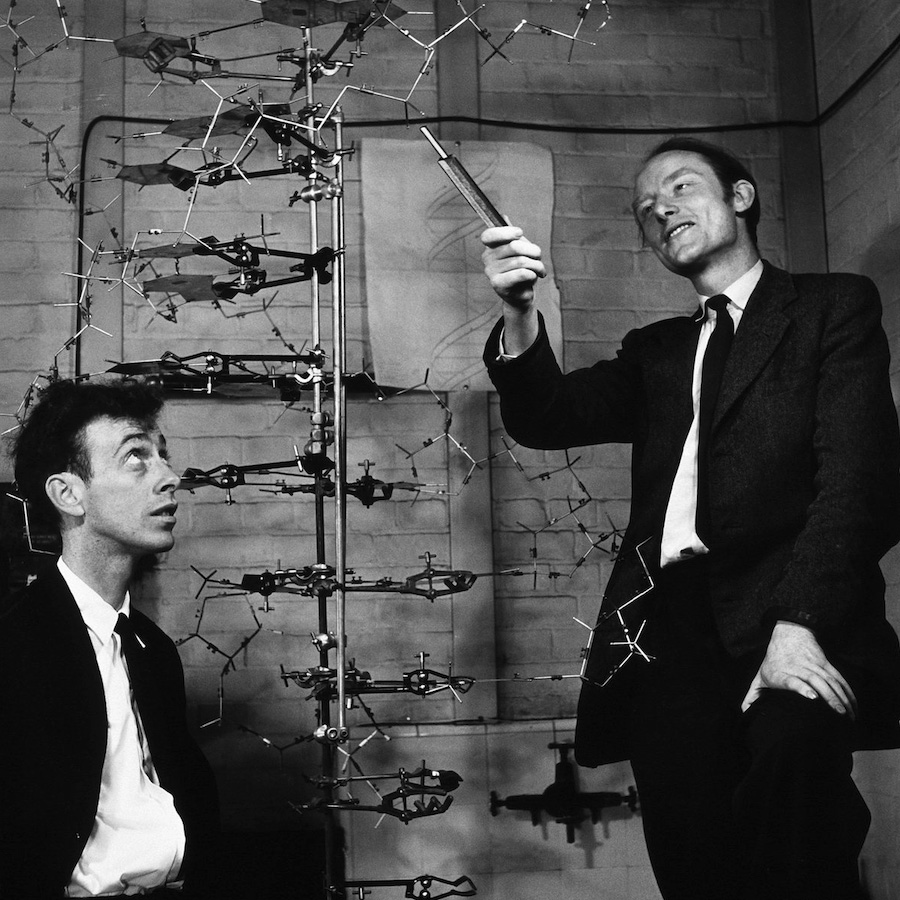

Critical events: Now, the stage should have shifted to studying the structure of DNA itself. Except that only a few research teams took up this challenge. Watson and Crick were one of those teams — they were consumed by this question. They met at Cambridge University. Crick was a graduate student, a physicist retraining in biology, and Watson was doing postgraduate work on the structure of the protein hemoglobin. After reading about Pauling’s work, they wondered if DNA might also be some sort of helix. They also worried (correctly) that Pauling would be turning his attention to DNA soon. So there was a race.

Unfortunately, Pauling had the resources to actually do research and a mandate to study what he wanted. Watson and Crick were two nobodies. Besides, another British laboratory had the mission to study the structure of DNA – Rosalind Franklin in London. So Watson and Crick were poaching. Still, they persisted. They believed that DNA held the secret of life – of genetic replication – and they wanted to discover that secret by discovering the structure of DNA. They knew that a single strand was not sufficiently complex to carry information, and they didn’t see how a double strand of DNA might work, so they speculated that it was a triple helix. The strategy Watson and Crick used was to build a conceptual model of DNA, creating a three-dimensional representation. They invited Franklin up to Cambridge to view their model, and she shot it down, pointing out its implausibility. So the head of their laboratory at Cambridge ordered them to stop working on DNA.

Then they got a preliminary paper by Linus Pauling proposing a structure for DNA. It was also a triple helix and contained some of the same flaws that theirs had, so they knew they still had a head start on Pauling.

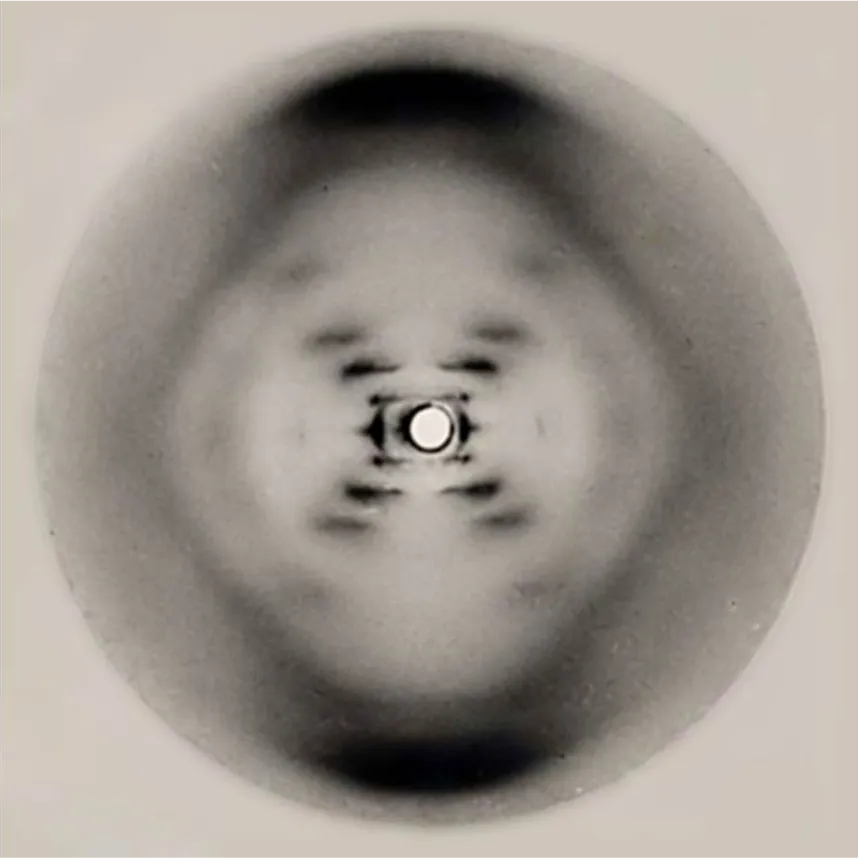

In addition, Watson got a look at one of Franklin’s X-ray crystallography photographs of DNA and immediately saw, to his satisfaction, that it was a helix. Despite the warning to stay away from DNA, they went back to work, building physical models of DNA. Crick tried to make the triple helix form, and Watson focused on the double helix form. The machine shop at Cambridge had not yet prepared the 3-D materials Watson needed for his double helix model, so while he was waiting, he played around with some 2-D cutouts.

Insight: As Watson was playing around with some of the physical model components, he was startled to find that an adenine-thymine pair held together by two hydrogen bonds had the identical shape as a guanine-cytosine pair held together by at least two hydrogen bonds. Essentially, adenine bonds only to thymine, and cytosine bonds only to guanine. In that instant, the double-helix model sprang to life for Watson. Now he appreciated the significance of Chargraff’s findings that in DNA the proportion of adenine and thymine matched the proportion of guanine and cytosine. Watson had solved eight puzzles simultaneously. He knew the structure of DNA – a helix. He knew how many strands, two. It was a double helix. He knew what carried the information – the nucleic acids in the gene, not the protein. He knew what maintained the attraction – hydrogen bonds. He knew the arrangement: The sugar-phosphate backbone was on the outside, and the nucleic acids were on the inside. He knew how the insides matched – through the base pairs. He knew the arrangement – the two identical chains ran in opposite directions, so they were mirror images — complementary pairing. And he knew how genes replicated themselves, through a zipper-like process. [Note – this is Watson’s version.] Crick’s version is somewhat different. Crick appreciated the complementary pairing way before Watson discovered it. Watson had been fixated on a like-with-like pairing until his insight in the laboratory. Crick also had appreciated the significance of Chargraff’s research when he first heard about it, when he and Watson had lunch during a visit Chargraff made to Cambridge, and Crick told Watson about it, but Watson wasn’t listening properly.

Being Oblivious

The story of the discovery of DNA is well known, but it usually doesn’t recount the failures as well as the successes – the reasons why others didn’t catch on, the flawed data that misled them, the flawed beliefs that blinded them.

Fixation. Researchers at the time had long believed that genes were coded by a protein because proteins have complex structures, and it makes sense that something as complex as genetic transmission would depend on a complex entity. As stated above, Avery, a bacteriologist, had reported that bacterial DNA embodied the bacterial genes. However, the scientific community didn’t trust Avery’s findings because his study was not perfectly controlled. Scientists were prejudiced against DNA because it was seen as stupid, a backbone, just too simple, and not a means of carrying and coding information. After all, DNA only had four bases. The leading researchers of the time, Perutz, Delbrück, and Luria, all missed the implications of the Avery data. They lacked the right frame. It wasn’t until the Hershey findings from 1952 that the researchers started to become curious about DNA, but even then, it was hard to give up their original orientation towards proteins as carriers of genetic information.

Parochialism. Few of the scientists were even equipped to start down the right path. Luria and other genetic researchers didn’t know biochemistry or care about it; they were just interested in the characteristics of genes. So their investigations were limited by their parochialism.

Bad data. Linus Pauling was thrown off by bad data about the hydrogen bonds, just as Crick and Watson had been. Watson and Crick recovered because they had a colleague who could correct them, Jerry Donohue.

Bad luck, and recovering from bad data. Enter Jerry Donohue. Watson and Crick were using the enol configuration for bases, but Donohue showed them that they should have been using the keto configuration. Donohue also revealed that the textbook data were wrong! [This also tripped up Linus Pauling.] All at once, Crick’s aversion to hydrogen bonds disappeared. It all came clear to Crick when Donohue put them onto the keto form.

A failure to see implications which is a form of stupidity. Chargraff had the pieces for the discovery — his research showed that in DNA, the proportion of adenine and thymine matched the proportion of guanine and cytosine. That was such a critical clue. But Chargraff didn’t imagine the implications of his ratios. Pauling also knew about Chargraff, but he also didn’t see the implication. In contrast, when Watson and Crick met with Chargraff and heard about the ratios, Crick was electrified! Right away, he saw the implication for how replication might occur. It was in keeping with Crick’s functional and dynamic orientation. In contrast, Watson barely remembered the meeting until Crick later reminded him.

Arrogance. Watson and Crick lacked status. Watson was a postdoc, and Crick was just a graduate student. Rosalind Franklin wouldn’t collaborate with them or take them seriously, and also didn’t believe DNA was a helix. Chargraff wouldn’t collaborate with Watson and Crick because he thought them dabblers, which they certainly were.

Blindness/stupidity, stemming from fixation. In Franklin’s annual report on her research, she presented a key datum, “monoclinic face-centered.” The implication was that the chains ran in opposite directions. Crick got it. Franklin (and Watson) didn’t.

More bad luck. There are two DNA forms, dry and wet. Some previous work on DNA had mixed these, generating more bad data. Franklin’s focus on the alpha form misled her. If she had gone directly to the wet form, she might have cracked the riddle of DNA. Another piece of bad luck is that Franklin found an unusual DNA variant and went off on that, but it was a false trail.

The wrong frame. Franklin’s famous 51 photo, an X-ray crystallography image, showed DNA as a helix. Franklin let the photo sit for 10 months (!!) before she saw the implication. Watson saw the implication immediately upon seeing it. (Small scandal here — Watson should not have been shown photograph 51, but we will pass that by.) Why? Because Watson was already thinking about a helix. Photo 51 showed helix, plus it showed the spacings — the key dimensions. Further, Franklin was openly skeptical about a helix and was hoping to show that DNA was not a helix (another example of fixation). At one point, Franklin thought she had disproven the helix notion and titled a short note “Death of DNA helix.”

The wrong perspectives. How do the DNA strands go together? Franklin approached this from the perspective of crystallography, which is static. Franklin was close, but still two key steps away: pairing and complementarity. Crick had been homing in on complementary pairing ever since the summer of 1952 and the Chargraff visit.

Franklin didn’t come out of a model-building tradition (Watson did). She wasn’t thinking about the constraints with regard to interatomic distances and angles, which reduced the free parameters. Watson and Pauling took a model-building focus, which was also static and geometric. In contrast to everyone else, Crick’s perspective was functional – and dynamic. He was primarily interested in thinking about how a gene, probably DNA, worked to enable accurate replication.

Too often, the structure of DNA as a double helix takes center stage in the story. That’s the title of Watson’s book. But according to Crick, the key to the discovery was how the base pairings were complementary, and not the helix shape. Complementary pairing meant that one strand of DNA could replicate a mirror image, but running in the reverse direction because the adenine-thymine pair held together by two hydrogen bonds had the identical shape as a guanine-cytosine pair held together by at least two hydrogen bonds.

In contrast, a like-with-like pairing (e.g., Adenine on one strand pairs with adenine on the other strand) wouldn’t work, for several reasons: the hydrogen bonds would be unstable, and also the possibility of transcription errors would increase. Further, the shape of the DNA strands would become irregular because of the different sizes of the bases. But perhaps the major problem with like-with-like pairing is that it wasn’t consistent with Chargraff’s finding that the amount of Adenine always equals the amount of Thymine, and the amount of Guanine always equals the amount of Cytosine.

Watson’s account focused on the double helix — possibly because Watson was the one who spotted that, not Crick.

Also, there was some good luck: the DNA bases are flat, so Watson really could model them in 2-D. He was doodling with the 2-D representations, waiting for the machine shop to finish the 3-D forms, when he stumbled upon the complementary pairings. Watson was lucky to have found the base pairing relation, given the number of faulty ideas he had (particularly like-with-like pairing, as opposed to complementary pairing).

The chronology starts when Watson heard Wilkins give a talk at a scientific conference, and realized that DNA could be solved, because it has a repeating structure. So Watson quickly got started on the right track, looking at DNA, and believing that it was possibly the gene. He had the right mindset, as opposed to all the others who had to recover from the protein-as-gene mindset.

Watson and Crick also made up a good collaborative team. They both believed that cracking the structure of DNA was likely to solve the puzzle of life, and that DNA was likely a helix, and that they could use modeling methods to discern its structure. But they were also good complements to each other. Crick was thinking of genes, not DNA. Watson was thinking of genes and DNA. Crick’s background: physics, x-rays, proteins, gene function. Watson’s background: biology, phages, bacterial genetics. Crick was the only crystallographer interested in genes. Watson was the only one in the phage group interested in DNA. They asked the right question – what is the structure of DNA?

The Watson Crick strengths: abandoning bad ideas quickly; strong focus on getting the structure of DNA, lots of different fields to blend, ability to sustain the necessary dialog. Few others were approaching these issues.

Recovering from stupidity. Crick’s first triple helix model was implausible because there wasn’t enough water. Basic chemistry showed that. Watson had misremembered what he had been told. Crick blamed himself for not appreciating the problem. They were made to look ridiculous when Rosalind Franklin visited their lab, and Franklin pointed out the error.

Recovering from a wrong idea. Late in the game, Watson started to warm to the idea of 2 rather than 3 backbones, but he still saw them on the inside. He really clung to the like-with-like mental model for replication. He wasn’t really getting Crick’s enthusiasm for complementary pairing until he stumbled upon it himself.

In conclusion, we see a variety of barriers that prevented all the talented scientists of the day from making the Watson-Crick discovery. These kinds of barriers must be operating in most situations, which should give us some ideas for how to breach these barriers, and should deepen our appreciation of the people who do formulate insights.

We can also appreciate the strengths of the Watson-Crick team. Building a three-strand model, but also deciding to check out a two-strand model just to be safe.

And we can appreciate Crick’s functional perspective — wondering how a substance with only four bases could reliably replicate itself, and how it could provide the building block for proteins. Crick wasn’t just wondering about the shape of DNA. He was the only scientist in this group trying to imagine how DNA could work.

References:

Crick, F (1988). What mad pursuit: A personal view of scientific discovery. Basic Books.

Judson, H.F. (1996) The eighth day of creation: Makers of the revolution in biology. 20th anniversary edition. Cold Spring Harbor Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

Watson, J. (1980). The double helix: A personal account of the discovery of the structure of DNA. W.W. Norton: New York.