OODA Versus RPD: Reconciling Models of Cognition and Conflict

John Schmitt provides a comprehensive beak down of the overlap and distinct differences between Boyd's OODA model of conflict and Klein's RPD model of cognitive decision making, and describes the contexts in which they are best suited.

I am sometimes asked about the relationship of the OODA Loop to Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM) in general and Gary Klein’s Recognition-Primed Decision (RPD) model in particular. Usually, the asker is a fan of all three searching for a way to integrate them into a unified theory of decision making. Is the OODA Loop a naturalistic model of decision making? What is the relationship of OODA to RPD? Do they somehow nest together, one within the other? Or do they overlap, and how? Are they different models but compatible, or do they contradict each other?

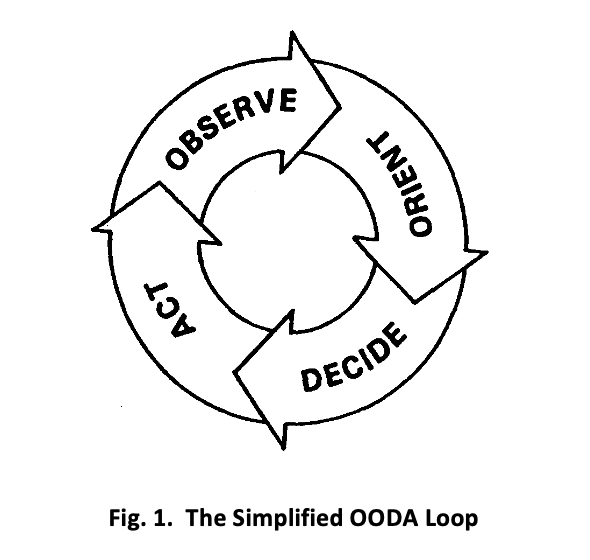

For the uninitiated, the Observation-Orientation-Decision-Action (OODA) Loop is the conception of the late Colonel John R. Boyd, arguably the most influential American military theorist of the late twentieth century. OODA is the centerpiece of Boyd’s theory on war and warfare. An Air Force fighter pilot, Boyd developed the OODA concept from his experiences of air-to-air combat and later extrapolated it to warfare more broadly. According to Boyd, any belligerent in a conflict first observes the situation by taking in information about it. The belligerent next orients to the situation by interpreting and assessing those observations. Based on that orientation, the belligerent decides what to do and then acts on that decision. See Figure 1.

By acting, the belligerent has changed the situation, and so the process begins again. This cyclical/temporal element is central to the concept. Boyd said that the idea was to “Observe, Orient, Decide and Act more incongruously, more quickly, and with more irregularity” to “[g]enerate uncertainty, confusion, disorder, panic, chaos [in the adversary] … to shatter cohesion, produce paralysis and bring about collapse” (Boyd, 1987, 132). To convey the idea, Boyd introduced the term “fast transients”:

- Idea of fast transients suggests that, in order to win, we should operate at a faster tempo or rhythm than our adversaries—or, better yet, get inside adversary’s Observation-Orientation-Decision-Action time cycle or loop.

- Why? Such activity will make us appear ambiguous (unpredictable) [and] thereby generate confusion and disorderamong our adversaries—since our adversaries will be unable to generate mental images or pictures that agree with the menacing as well as faster transient rhythm or pattern they are competing against. (Boyd, 1987, 5. Emphasis in original.)

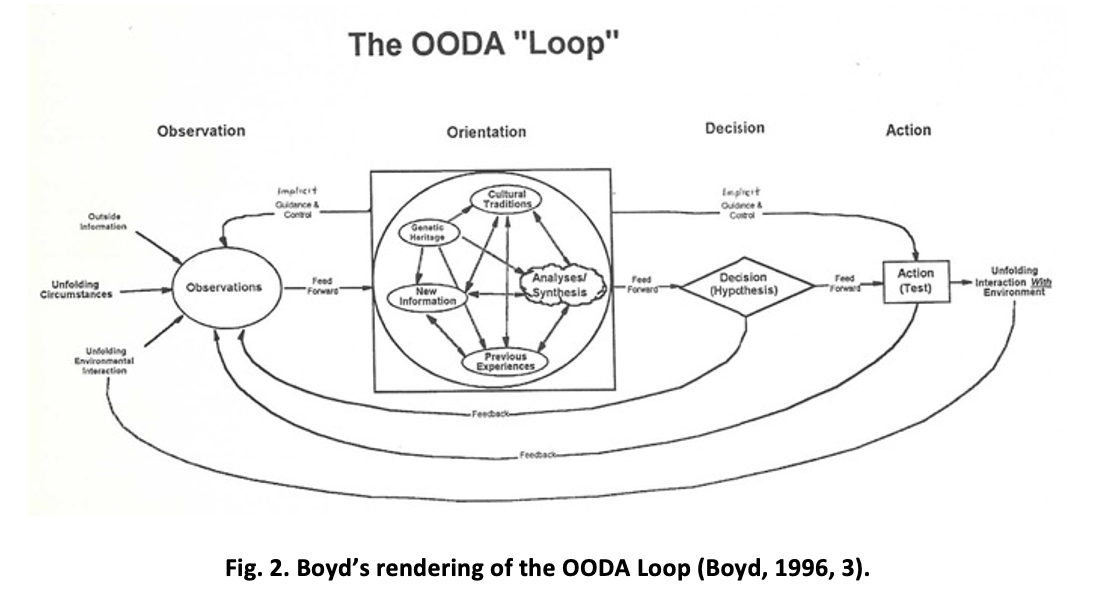

Because of this cyclical component, OODA is sometimes also referred to as the “Boyd Cycle” or “Decision Cycle.” This is admittedly a simplification of the concept. Boyd did not depict the OODA Loop until this very last briefing, “The Essence of Winning and Losing,” not long before his death in 1997. That final version was much more sophisticated, as indicated by Figure 2 below.

Boyd famously refused to commit his ideas to writing but presented them in the form of briefing slides, which he elaborated extensively and modified continuously through narration. As a result, any recounting of Boyd’s work is necessarily an act of interpretation.

Anybody reading this essay is probably familiar with Gary Klein’s RPD, but in the interest of completeness I will summarize it here. Klein was a pioneer in the 1980s of the Naturalistic Decision Making movement, which sought to study practical decision making in the real world as opposed to in the controlled settings where the research that had led to Rational Choice Theory had earlier taken place. (Read my previous discussion of RCT.) Klein did not set out to debunk Rational Choice Theory. He expected to see it validated in the field but found that practitioners rarely made decisions by developing and comparing multiple courses of action. He developed the RPD model to describe how he observed practitioners actually making decisions.

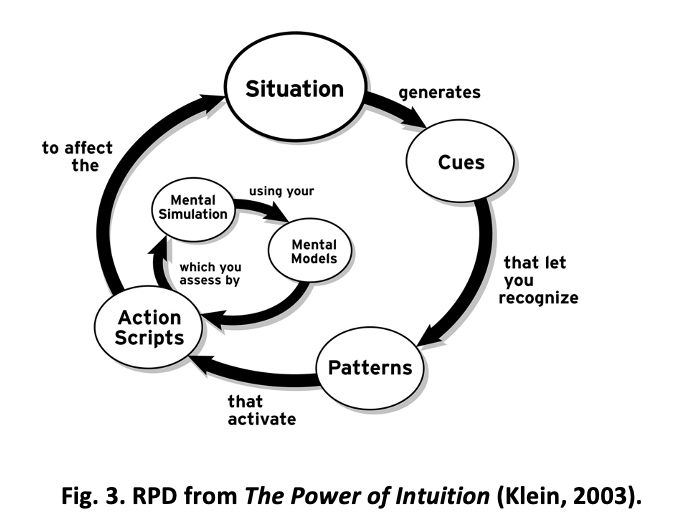

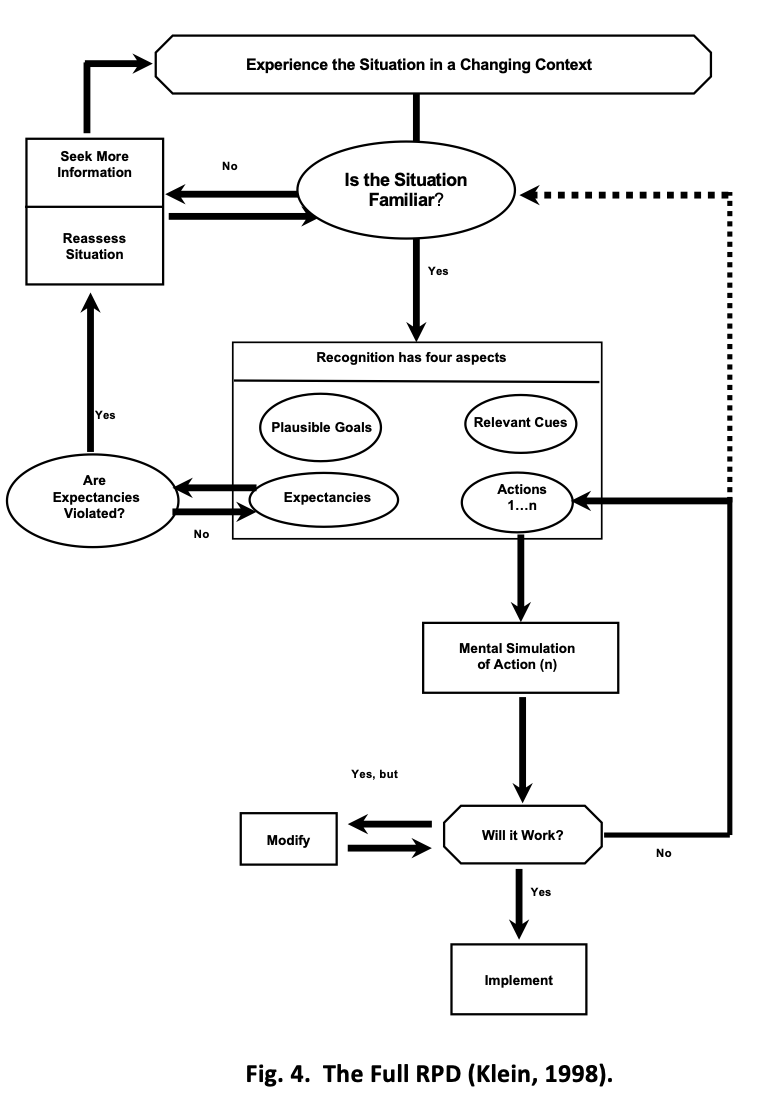

According to the RPD, a practitioner finds herself experiencing a situation in the world. Based on the cues she sees, she searches her past experiences for a pattern match and reviews what she did in that situation. If that course of action immediately seems to be a good fit for the current situation, she executes. If she’s not sure, she may run a mental simulation of that course of action against the current situation, possibly modifying it as needed. If the simulated course of action is satisfactory, she executes. If she cannot envision a satisfactory outcome, she goes back into her experience base to find a better pattern match, and the process repeats. If she cannot find a satisfactory pattern match, she reassesses the situation to see what she may be missing. An experienced practitioner can often rapidly find a satisfactory first course of action, but the model allows for considering multiple options. However, the practitioner considers those courses of action in sequence and adopts the first one she finds satisfactory—a process called satisficing. This contrasts with Rational Choice Theory, according to which the practitioner develops and compares multiple courses of action in parallel in (usually futile) pursuit of an optimal solution. Figure 3 shows a simple rendering of the RPD from Klein’s second book, The Power of Intuition.

There is a certain OODA-like quality to this version of RPD, which may encourage the comparison. Like Boyd, Klein developed a fuller version of his model, complete with feedback loops, as shown in Figure 4 below.

There have been multiple attempts to settle the issue of how OODA relates to NDM and RPD. I am happy to give my opinion as somebody who has known both Boyd and Klein and talked to them about their work.

My short answer is that OODA, NDM, and RPD are different types of things. While they are generally compatible, I see no utility in trying to merge or correlate them. First of all, NDM is a broad field of study looking at how people make decisions in the real world under conditions of uncertainty, time pressure, and other stresses. It is not a model but a field of research with several models in it. Klein’s RPD is one of those models. RPD is a descriptive model of how human beings make consequential choices in the world based on experience. It is a human cognitive model. As such, it is typically understood to take place within the mind of an individual decision maker (although I don’t think it is much of a stretch to apply it to team decision making).

The OODA Loop, even though it is sometimes called a decision cycle, is not a cognitive model of decision making at all. Viewed narrowly, a spinning OODA Loop is a generalized model of adaptation to (usually hostile) surroundings. In that sense, OODA applies not only to warfare, but to any situation in which an entity with freedom of action acts to improve its fitness in relation to the surrounding environment, which includes other entities with competing interests. It can apply to a single human, but it also applies equally to groups or organizations large and small. For that matter, it can even apply to simple organisms, and in that sense, it is not necessarily about decision making in a cognitive sense at all. More ambitiously, as captured in Boyd’s words above, the OODA concept in the context of conflict can be viewed as a theory of victory based on triggering the internal collapse of the hostile OODA Loop.

The RPD describes how a human reaches a single decision. It does not emphasize OODA’s cyclical element of acting on the decision to create a new reality to be observed, oriented to, decided about, and acted upon. Although RPD describes how practitioners often can make decisions quickly, there is no “fast transient” element to it. This is no criticism of the RPD, which is intended to describe the internal process of reaching a decision, not to describe the time-competitive, mutually adaptive dynamic of conflict. That said, there is no reason RPD cannot be applied cyclically to each new decision resulting from the previous one.

Meanwhile, OODA is agnostic about how the “decision” actually gets made. While Boyd was familiar with Klein’s work and clearly had a naturalistic view of human decision making, he did not specify a decision model within the D of OODA. It could be through use of RPD, or it theoretically could be some other process—even Rational Choice Theory. Nor is this a criticism of the OODA Loop, for Boyd intended to present a model of competitive adaptation, not to describe a cognitive process.

OODA and RPD exist side by side but are not intertwined. Obviously, there is some overlap between them, as humans use their brains to make decisions when adapting. If forced to overlay the two, I would say that RPD generally coincides with the O-O-D of OODA, without the A or the feedback to the first O. But while the two models may be looking at some of the same things, they are doing so from different perspectives for different purposes.

Despite the overlap and the appeal of both models, I think it is best not to try to kludge them together into some kind of Franken-model. If you want to understand the process by which humans use their experiences to make choices under conditions of uncertainty, shifting goals, and time pressure, Klein’s Recognition-Primed Decision model is your ticket. On the other hand, if you’re after a theory of competitive adaptation over time as a path to victory, Boyd’s OODA Loop may be what you’re looking for.

References

John R. Boyd, A Discourse on Winning and Losing, unpublished briefing slides, August 1987.

John R. Boyd, “The Essence of Winning and Losing,” unpublished briefing slides, January 1996.

Gary Klein, The Power of Intuition: How to Use Your Gut Feelings to Make Better Decisions at Work, New York: Currency, 2003.

Gary Klein, Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998.