RPD: A Memoir

John F. Schmitt recounts how the Recognition-Primed Decision model validated his instincts, reshaped his understanding of battlefield command, and helped inform Marine Corps doctrine.

My colleague Jared Peterson’s essay, “A Primer on Recognition-Primed Decision Making (RPD),” got me thinking about my own experience with RPD. Turn the clock back to 1981: I was a brand-new second lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps, and I was determined to be the next Hannibal, the next Bonaparte, the next Rommel. Which is to say, I had ambitions to become a military genius. No immodesty there, certainly. It struck my young mind that the thing that separated the Great Captains of history from everybody else was the quality of their decisions, which I saw as the product of an uncanny ability to grasp a complex and chaotic battlefield situation—Frederick the Great coined the phrase coup d’oeil, literally “stroke of the eye”—and the creative intelligence to devise bold and decisive tactics or strategies ideally suited to that situation.

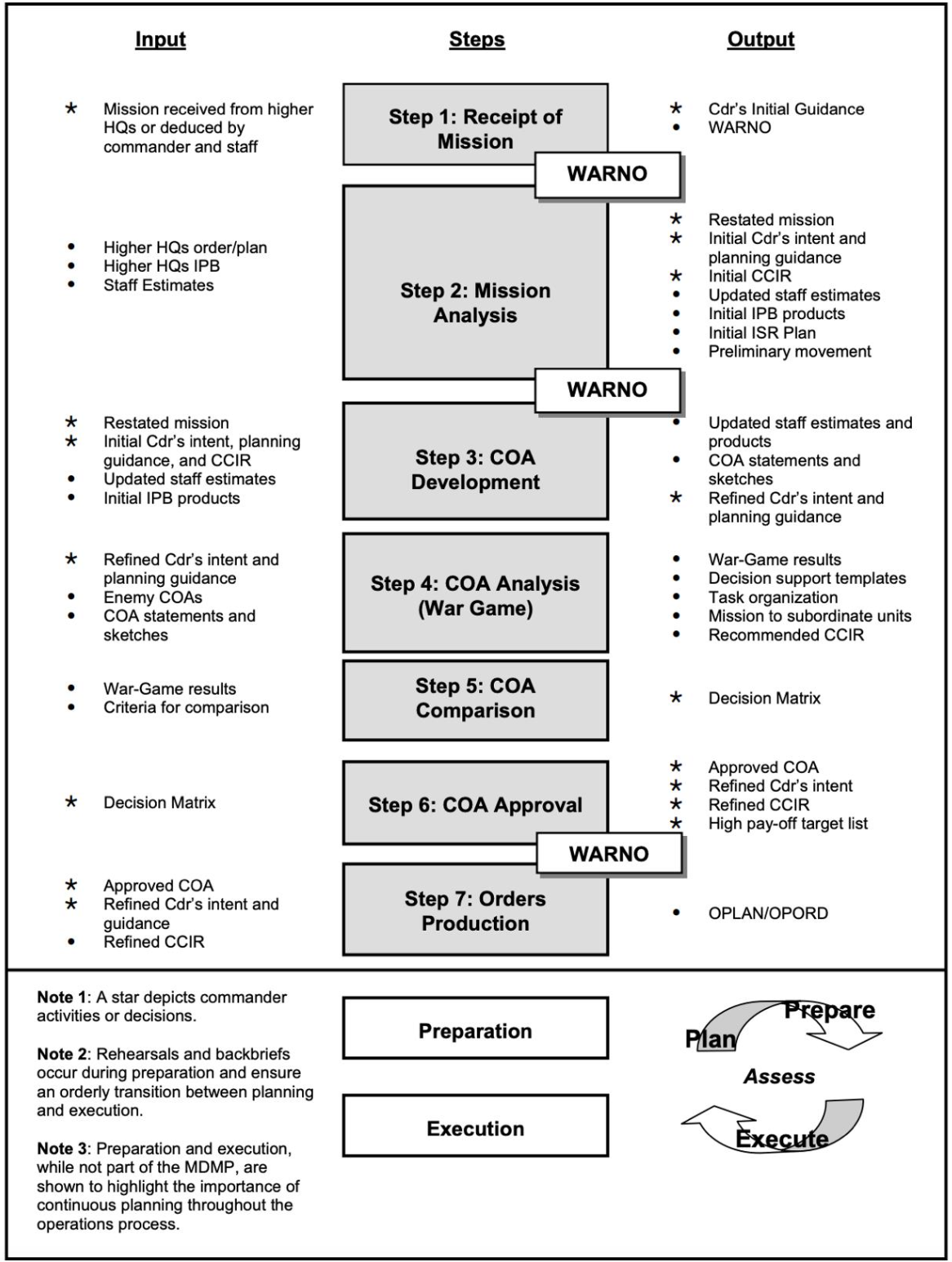

Imagine my excitement when, as a student at The Basic School (TBS)—the six-month introductory course in Quantico, Virginia, for all newly commissioned Marine officers—I saw we were to receive instruction in “The Military Decision-Making Process.” Finally, we were getting to the core of what it meant to be a commander. This obviously was going to be a key class, full of substance and central to our training. Instead, a captain recited from a script on the approved method for making decisions, which turned out to be a rote procedure known universally as “The MDMP.” First, you were to gather all the relevant information. Next, you would generate three courses of action, or COAs. Then you would establish a common set of evaluation criteria and create a matrix to rate each COA according to each criterion. The COA with the best aggregate score was your decision. The captain assured us that this was indisputably the optimal way to make decisions. It was proven. It was settled science. To do anything else was irresponsible. It was to be cavalier with the lives of your men.

The MDMP

It made no sense to me. As a platoon commander, in the middle of a firefight, with mere seconds at my disposal and lives at stake, I was expected to undertake this exercise in ranking and tallying? It seemed patently ridiculous. I had never made a decision that way in my life, and I doubted whether Hannibal, Bonaparte or Rommel ever had either. But what did I know? I was a mere second lieutenant. Who was I to question Authority? I was supposed to be soaking up collected wisdom, not questioning it. Certainly, the Marine Corps would not have taught me this if it weren’t true. I kept my mouth shut and left TBS thinking there was something wrong with me.

I went to the Fleet and got on with the practical business of leading Marines. Then an interesting thing happened: I discovered that nobody else used the MDMP either, even if they pretended to.

I recall one field exercise when I was serving on an infantry battalion staff. In a moment of unusual candor, the operations officer, a major, revealed the Majors Guild trade secret for generating COAs for a commander’s consideration. One COA would be the desired option, the one the commander was expected to choose. Another would be essentially the opposite of the first one, to highlight the first one’s advantages. The third COA would be some intentionally crazy, off-the-wall option that nobody in his right mind would pick. In case there was any question as to the preferred choice, it was a further unwritten rule that the preferred COA was presented as the middle option. It was all a kabuki dance—except that on that occasion the battalion commander picked the crazy, off-the-wall option because he thought that, being crazy and off-the-wall, it would catch the enemy by surprise. We did poorly in the field exercise that day.

By the time I made captain, I was confident the MDMP was not the answer and was willing to say so. But I didn’t know what was. Then, in 1990, I read an article titled “Strategies of Decision Making” in Military Review, the professional journal of the U.S. Army. The author, a cognitive scientist named Gary A. Klein, blew the lid off the MDMP, putting into words all the things I intuitively sensed were wrong with the model. In its place he proposed the Recognition-Primed Decision model: practitioners made sense of situations and made decisions by recognizing patterns, critical cues, suitable objectives, and potential solutions from past experience. They did it intuitively, sometimes even without realizing they were doing it. They did it without generating and comparing multiple courses of action. It is no exaggeration to say it was a revelation. Here was this white-lab-coated academic with no military experience—no man of action like myself—describing precisely what occurred in my brain, and in a way that validated what I had been doing all along.

I later learned that the white lab coat thing was inaccurate and unfair. The key to Klein’s research is that he took it out of the controlled environment of the laboratory and brought it to the wild, where he observed actual practitioners making consequential decisions under uncertainty, time pressure and other stressors. This, of course, was the genesis of the Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM) movement, of which he is one of the pioneers.

By the way, apparently not satisfied with describing my internal decision-making process in detail, Klein later claimed to have successfully reverse-engineered my entire tactical system from reading my book Mastering Tactics. (Shades of Patton, in which George C. Scott as the title character famously says upon meeting the Afrika Korps in battle: “Rommel, you magnificent bastard, I read your book.” That book was Infantry Attacks, a classic on decision making in battle.)

I asked myself: If RPD was an accurate description of the decision-making process, what then were the implications for my continuing Hannibal-Bonaparte-Rommel quest? First, if the process occurred naturally, there was no need to practice the steps, which is how the MDMP was traditionally taught. Second, according to RPD, the key to effective decision making was experience. The bigger your experience base, the more patterns, critical cues, suitable objectives, and potential solutions you had at your disposal. The trick to becoming the next Hannibal, Bonaparte or Rommel thus lay in accumulating as many meaningful, relevant experiences as possible, whether actual, simulated or vicarious. Enter TDGs.

It would be a better story to say that this insight led me to tactical decision games (TDGs), but the truth is that by this point I was already experimenting with TDGs, as both a way to exercise tactical decision making and a way to explore the application of maneuver warfare concepts. (Maneuver warfare was the new operational doctrine the Marine Corps had recently adopted.) The value of TDGs in improving decision-making skills had seemed intuitively obvious; now the RPD explained why, providing a scientific basis for the extensive use of TDGs throughout the Marine Corps to this day.

In 1996, I authored Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication (MCDP) 6, Command and Control, the Marine Corps’ foundational manual on the practice of command. In the chapter on “Command and Control Theory,” the manual adopts the RPD as an accepted model of decision making. (Among other things, it was an attempt to drive a stake into the heart of the MDMP. I thought “Recognition-Primed Decision model” would sound too social-sciency to most Marines, so I chose “Intuitive Decision Making,” but it is essentially a description of the RPD.)

“Strategies of Decision Making” led me to make contact with Klein, which has resulted in a collaboration that has lasted over three decades. The MDMP is merely one of the windmills we have tilted at. In reality, the MDMP is less a model of decision making than it is a staff planning procedure built around the rational choice theory of decision making. Staffs require procedures to efficiently guide and coordinate their efforts. No dispute. The problem as we saw it was that the MDMP was built around an erroneous model. Our intent was to provide a staff procedure based on the RPD. We called it the Recognitional Planning Model (RPM). (The connotation of speed was intentional.) We wrote a manual. It caused a little bit of a stir at the Army’s Battle Command Battle Lab in Ft. Leavenworth, but in the end it didn’t stand a chance against Big MDMP. I could probably find a copy somewhere.

Looking back, what began as an intuitive resistance to a rigid, mechanical model of decision making has evolved into a decades-long pursuit of understanding how practitioners make decisions under pressure and how to help them get better at it. The RPD model not only validated my early instincts but also offered a language and framework that matched the reality of military command. From the classroom at TBS to the field, from TDGs to doctrine, the RPD model has shaped the way I think, teach, and lead.

Today I run ShadowBox, the company Gary Klein founded to use experiential decision-making exercises to improve cognitive skill. It has been a long time since those early days in Quantico, but in my mind I have not given up on completely the Hannibal-Bonaparte-Rommel quest. I want to be ready in case the balloon goes up.